There's a moment in every classification project where you watch the model confidently get something wrong. Not a hard case. Not an ambiguous edge. Something a human would solve in half a second without thinking.

You check the prompt. The class is defined. The definition is accurate. The model read it, understood it, and still chose wrong. You add a clarifying sentence. Maybe an exception. Maybe a "do not confuse with" or "IMPORTANT" clause. It works for that case. Then a new failure arrives, structuraly identical to the last one but just different enough that your patch missed it.

This is the prompt engineering treadmill. We've been on it. We've added hundreds of lines of classification instructions, watched accuracy climb then plateau. Edge cases kept piling up and the prompts got so long that the model began to ignore important parts.

At some point we stopped and asked a different question: what if describing classes isn't the right approach at all?

The answer became HoloRecall. A system that teaches classifiers through examples rather than explanations. Instead of writing ever-longer definitions, we show the model what each class looks like.

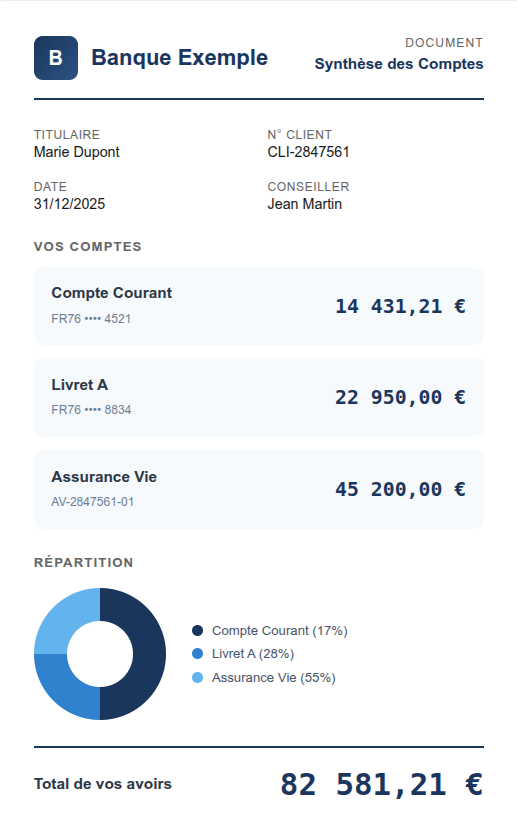

This is how humans actually learn document types. Think about onboarding a new analyst to classify bank documents. You don't hand them a manual defining "Bank Statement" versus "Account Summary" in abstract terms. You sit them down with examples: "This is a bank statement. See the transaction table, each row has a date, description, and amount. Running balance on the right. This is an account summary, no individual transactions, just balances grouped by account type, maybe a pie chart. Both come from the same bank. Both have account numbers and dollar/euro amounts. But look at the structure. You'll learn to recognize them."

That's what HoloRecall does for your classifier.

Bank statement: Transaction-level detail, running balance.

Account summary: Aggregated balances, no individual transactions.

What they share: Account numbers, dates, balances—often from the same bank. Semantic overlap is high. Visual similarity is low.

The prompt engineering treadmill

Let's be specific about what goes wrong.

You're classifying financial documents. You have a category called "Bank Statement" and another called "Account Summary." Both can contain account numbers, balances, transaction lists. The semantic overlap is real. So you write careful definitions: bank statements show transaction-level detail with dates and amounts; account summaries aggregate balances across accounts without individual transactions.

It works. Mostly.

Then a bank sends a "Statement of Account" that's formatted like a summary but contains transactions. Then another bank sends a "Monthly Summary" that's actually a full statement. Then a third bank sends something that's genuinely ambiguous even to humans—and your classifier picks confidently and wrong.

Each failure teaches you something. You encode that lesson in the prompt. The prompt grows. You add examples in the instructions: "A Bank Statement typically looks like X. An Account Summary typically looks like Y." But "typically" is doing a lot of work, and exceptions keep appearing.

The fundamental issue isn't that the model is stupid. It's that language is an inefficient encoding for visual patterns. You're trying to describe, in words, differences that humans perceive instantly through layout, structure, and spatial arrangement.

Prompts capture semantics well. They capture visual structure poorly.

The many-classes problem

This gets worse as taxonomies grow.

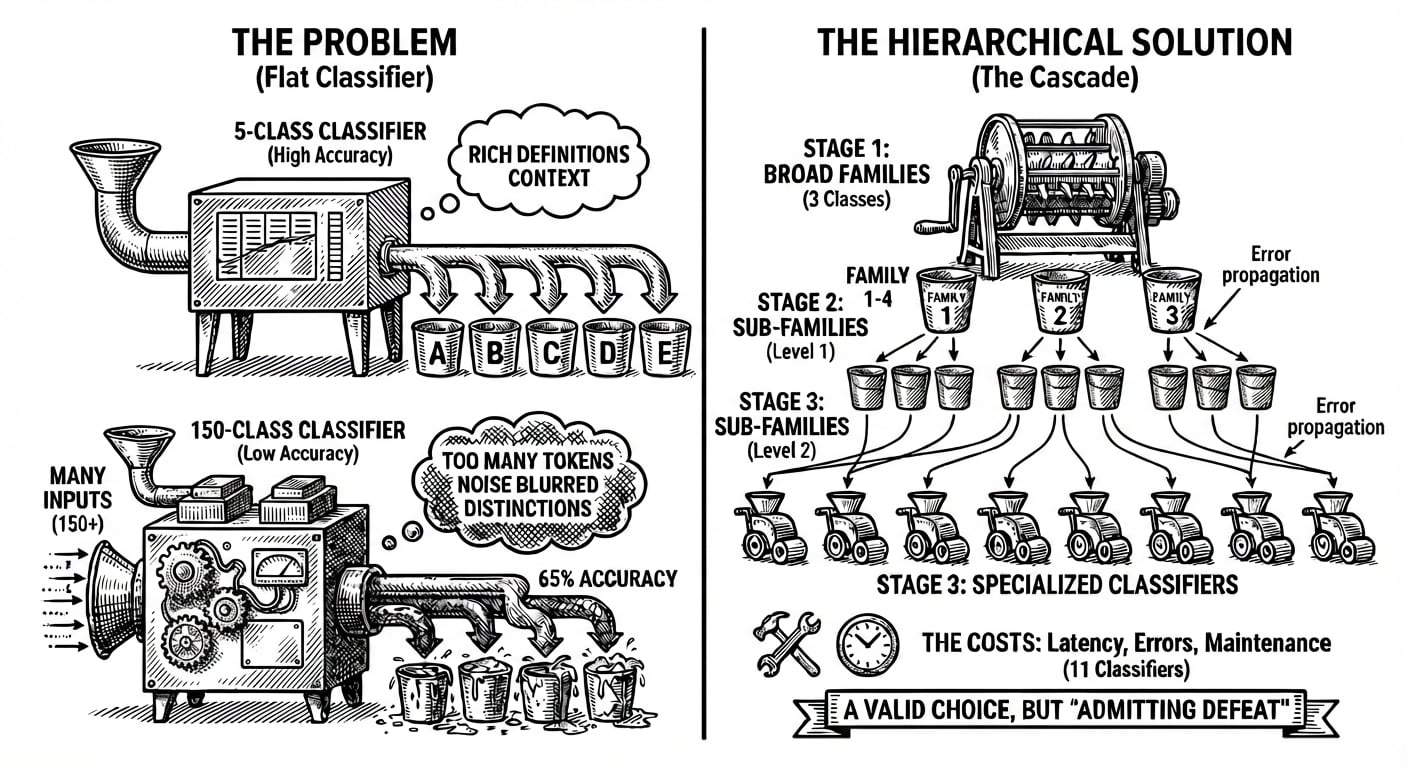

A classifier with six categories can include rich definitions for each one. The model has plenty of context to understand what makes each class distinct. But what happens when you have 50 categories? Or 150? Or 300?

Every definition consumes tokens. Every token competes for the model's attention. At some point, you're not adding clarity, you're adding noise. The model has to hold so many class descriptions in context that the distinctions between them blur.

This is a fact that has been proven. When researchers tested classification accuracy across datasets of varying complexity, a clear pattern emerged: models achieved over 94% accuracy on a six-class sentiment task but dropped to around 65% on a 119-class app categorization task. Same underlying model. Same training approach. The difference was taxonomy size.

The obvious solution is hierarchy. Instead of one classifier choosing among 150 classes, you build a cascade: first classify into 10 broad families, then route to a specialized classifier for each family. This works. we’ve built these systems and seen meaningful accuracy gains in practice. In fact, Holofin is introducing this approach as part of our upcoming Workflows feature (watch for a dedicated article soon).

But they come with costs. Every stage introduces latency. Every stage can propagate errors. If the first classifier assigns a document to the wrong family, no amount of precision in the second stage will save it. And maintenance becomes a headache: now you're tuning 11 classifiers instead of one, each with its own prompt, its own edge cases, its own failure modes.

Hierarchical classification is a valid engineering choice. It's also, in a sense, admitting defeat to the prompt engineering problem.

We wanted something different. Something that scaled without multiplying prompts.

Why reasoning doesn't help here

In tasks like math and code generation, chain-of-thought reasoning helps. Classification doesn't work this way. Recent research—and our own results—found that adding reasoning steps either made no difference or actively hurt performance. When models "think" before classifying, accuracy dropped. When they output the class first and explain after, accuracy went up.

This makes sense when you consider how humans classify documents. You don't reason your way to recognizing an invoice. You glance at it and know. Recognition is fast, automatic—pattern-matching, not deliberation.

Classification needs exposure to patterns, not elaborate explanations.

Visual similarity ≠ semantic similarity

Traditional retrieval matches on meaning. This works for search and question-answering. It fails for document classification.

Remember the bank statement and account summary from earlier? Both contain account numbers, dates, balances. Both come from the same bank. Semantically, they overlap heavily. But visually, they're distinct: transaction tables versus aggregated summaries, running balances versus grouped totals.

For documents, layout is the more reliable signal. Structure stays stable across instances of the same type. Text content varies. Describing classes in prompts is like explaining what a face looks like instead of showing a photograph.

HoloRecall: memory for your classifier

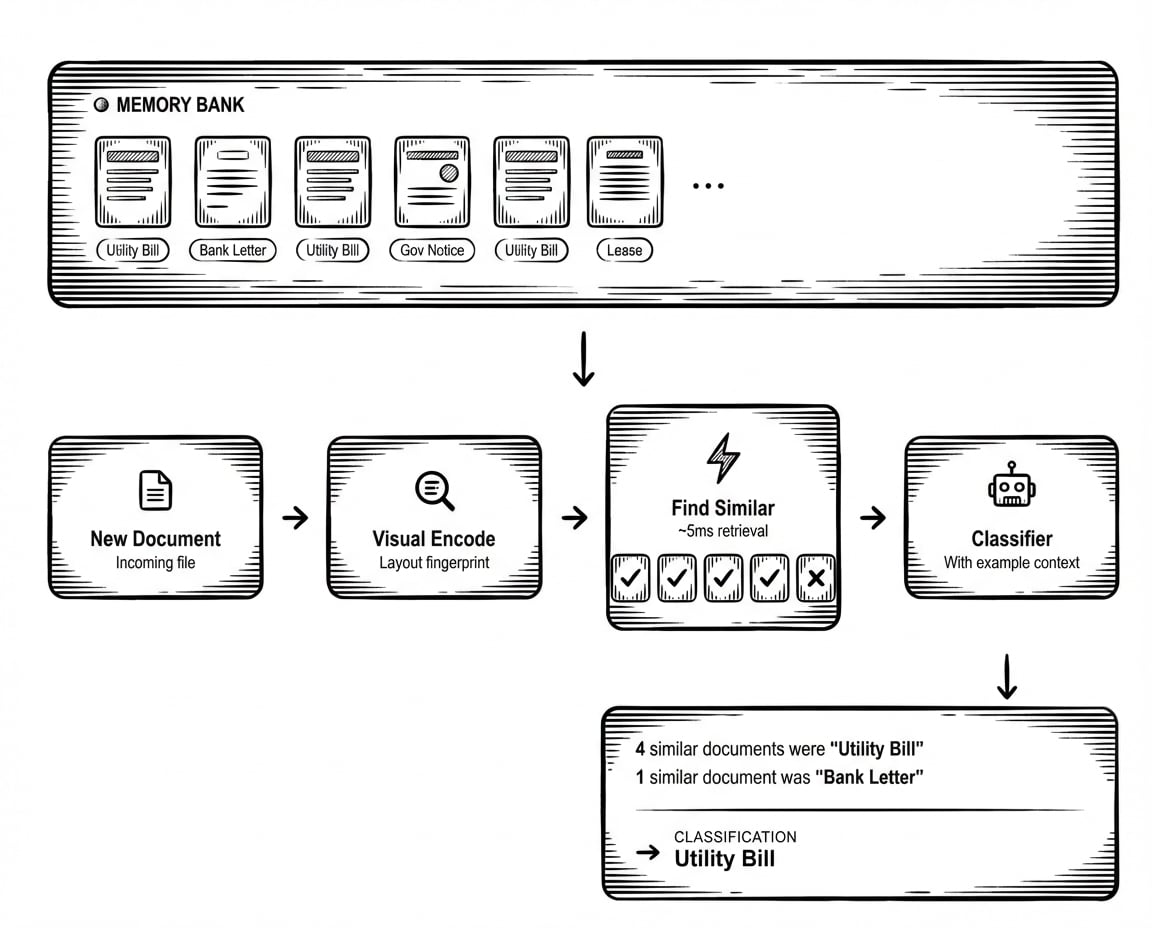

HoloRecall gives classifiers additional context: alongside descriptions of what each class means, examples of what each class looks like.

The idea is simple. Every time you validate a classification (confirming the model got it right, or correcting when it got it wrong) that document becomes a reference example. When a new document arrives, HoloRecall finds the most visually similar examples from this memory bank and injects them into the classifier's context.

Instead of the prompt saying "an invoice is a commercial document requesting payment for goods or services," the context now includes: "Here are five documents with similar layouts. Four were classified as Invoice. One was classified as Receipt." The model sees actual examples, not abstract definitions.

How the learning loop works:

When a user validates or corrects a classification, the document is encoded into a visual representation, a fingerprint that captures its structural layout, not just its text content. This fingerprint goes into a memory bank specific to that classifier. No retraining required. No prompt changes. The system simply remembers what it's seen.

How retrieval works:

When a new document arrives, it gets the same visual encoding. HoloRecall searches the memory bank for documents with similar structural fingerprints. This happens in milliseconds, fast enough that it doesn't meaningfully impact classification latency. The most similar examples, along with their validated labels, are retrieved and added to the classifier's context.

Why this scales:

Adding a new class still benefits from a good prompt definition, but now you can supplement it with examples. As your memory bank grows, your classifier sees more patterns, handles more edge cases, recognizes more variations. The system gets smarter passively, through normal usage, without code changes.

This is the compounding advantage: every document you process and validate makes the next classification slightly more informed. Your classifier develops institutional memory.

Where this changes things

HoloRecall isn't a replacement for good prompts. A well-defined classification taxonomy with clear, distinct categories will always be the foundation. But there are specific situations where memory provides leverage that prompts cannot.

Edge cases that resist description. Some document types are genuinely hard to define in words. The difference between a "proforma invoice" and a "commercial invoice" might have subtle layout cues that you recognize when you see them but struggle to articulate. Instead of writing ever more convoluted definitions, you show examples and let the visual similarity do the work.

High-cardinality taxonomies. When you have dozens or hundreds of classes, memory provides a scalable alternative to prompt bloat. You don't need to fit 200 class definitions into context. You retrieve the relevant examples based on visual similarity, providing targeted context rather than exhaustive documentation.

Vendor-specific layouts. Many classification problems have a long tail of vendor-specific formats. Bank A's statements look different from Bank B's. Carrier X's bills of lading have different structures than Carrier Y's. Memory learns these vendor-specific patterns automatically as you process documents from each source.

Getting started

HoloRecall is available today for classifiers in Holofin.

To enable it:

Navigate to your classifier's configuration page. In tab nav, locate HoloRecall. Toggle it on to begin building a memory bank from your previously validated classifications. You can also manually add representative examples for each class directly in the configuration. Once enabled, HoloRecall immediately starts learning from your dataset.

Building a good memory bank:

The quality of memory depends on the quality of examples. Start by syncing examples from your evaluation sets, these are already validated and representative. As you process documents and correct mistakes, those corrections become new examples. Over time, the memory bank accumulates coverage of your document landscape.

When to use it:

As we demonstrated, HoloRecall helps most when you have visual variation within classes, when your taxonomy is large, or when you're hitting accuracy plateaus that prompt refinement can't solve. If your classification is already performing well with a small, well-defined taxonomy, HoloRecall feature adds less value. Start with your problem cases.

Closing

We spent a long time believing that better classification required better instructions. More precise definitions. More edge case handling. More careful prompt engineering.

That belief wasn't wrong, exactly. Prompts matter. But they have limits. Limits that become visible when taxonomies grow, when visual patterns diverge from semantic descriptions.

HoloRecall comes from a different approach: We stopped trying to describe every edge case. We started remembering them.

Related Articles

The Invisible Audit Trail

An auditor opens your export file, finds a closing balance of €47,500, and pulls up the source PDF. Page 3, bottom-right corner: €47,000. Different number. "Where does the difference come from? Who changed it?"

Your LLM Isn't a Document Pipeline

There's a moment in every AI project where the demo looks so good that your brain quietly starts deleting code. You watch a model "read" a bank statement and think: this is it. We can skip OCR. We can skip layout parsing. Maybe we can skip half the pipeline. In the movie version, someone presses Enter and JSON waterfalls out of the cloud.

PDFs Are For People, Not For Data

We love PDFs. They look the same on every device, they print beautifully at any size, and they’re the closest thing we have to digital paper. But every time someone on our team says "let’s just extract the data from the PDF," we feel an ancient PostScript daemon wake up and whisper: “I was born to paint pixels, not to structure your rows.”